It had a terrible reputation but I was homeless and a temporary flat on a run down estate in central London looked too good an opportunity to pass by. My stay turned out to be a little longer than expected

‘Overflowing rubbish bins took centre stage’ ©AKC 1980

IT WAS LIKE walking into the pages of a magazine spread on modern-day slums. Rubbish bins stood in the centre of the courtyard, as if carefully arranged by the photographer for maximum effect, with the walls of the tenement forming a suitably grimy backdrop. Completing the picture, a line of washing hanging far above stretched from one side of the yard to the other, shirtsleeves flailing about in the breeze as if struggling for light.

It was midday but the only sign of life was the thud of music drifting out of an open window – otherwise the place appeared as deserted as the Marie Celeste. As I entered an open stairway to ascend to the first floor, a dank, musty smell hit my nostrils. Welcome to Hillview Estate in King’s Cross.

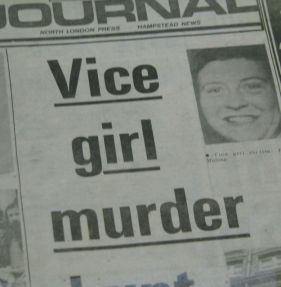

Tucked behind Camden Town Hall and a stone’s throw from the red-light district of Argyle Square, the seven blocks that made up the estate had been built at the turn of century to provide ‘model’ homes for the poor. It was now a notorious slum and criminal hang-out, regularly grabbing the headlines of the Camden Journal, where I worked as a junior reporter. A few months earlier, the place had reached its nadir with the brutal murder of a prostitute in one of the flats. The irony of my situation made me laugh inwardly – I was visiting the place, not as a reporter but as a prospective tenant.

It was autumn 1980 and my entry on to the estate was part of a council plan to hand over its 230 flats to youngsters as temporary housing under the aegis of Shortlife Community Housing, or SCH as it was always referred to. It was a plan born of desperation more than anything else. Camden Council had bought the estate in 1974 with the intention to renovate a part of it and knock the rest down. As tenants were moved out, empty flats were invaded by groups of hell-raising ‘punk squatters’, and then by more menacing elements who brought drugs and prostitution in from the seedy streets of King’s Cross.

In 1978, SCH began letting out flats on temporary or ‘shortlife’ licences to squatters and anyone adventurous, or foolhardy, enough to live there. The understanding was that once the council took the blocks back for demolition, the tenants would move out without the expectation of being re-housed. It was an arrangement that Camden and other inner London boroughs of the day frequently resorted to. In an ambitious spending spree a few years earlier, they had bought up huge swathes of semi-derelict property with the intention of doing them up. But the cash ran out and many of the properties were left empty.

At the same time, lack of housing for single young people due to a decline of privately rented lets had seen the birth of a huge squatters movement, which made it its business to take over the empty homes and create commune-type living. For councils, shortlife tenancies were a way of killing two birds with one stone – preventing council properties being squatted and providing housing. SCH had been set up in 1970 in response to the homeless crisis. Now it was to become one of the biggest players in shortlife housing.

The Hillview squatters came mainly from Huntley St off Tottenham Ct Rd, a famous squat of its day that was involved in a military-style eviction by hundreds of police in August 1978. Eighteen months earlier the empty mansion block had been occupied by 150 people and had become a cause-celebre, not only in drawing attention to the homeless problem but in signalling the growing momentum of the new counter culture.

Led by Piers Corbyn, brother of future Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, the squatters installed a café, hosted festivals and even opened an office, which helped to re-house the homeless. Their entry en masse was sanctioned by Camden’s ambitious new housing chief, Ken Livingstone. Like other Camden councillors, Livingstone was keen to see the estate knocked down but knew that in the meantime it made sense to fill as many flats as possible.

Those on the outside would have probably described shortlifers as “hippies” because of their wacky appearance. In fact many were university students and those on the first rung of the career ladder, while others were professional musicians and artists. There were also a sizeable number of Erirtreans, as well as the sons and daughters of local people who had been unable to get any other housing. According to newspaper reports, a number of missing youngsters from up north were eventually discovered living on Hillview too.

It took SCH almost a year to gain some degree of control of the estate as its staff ran the gauntlet of threats and attacks from those now facing eviction because of their criminal behaviour as well as from members of the fascist National Front.

The NF, which had been on the ascendancy throughout the ‘70s as Britain’s economic decline became more apparent, met locally in the Lucas Arms on the corner of Gray’s Inn Rd and Cromer St, and saw the youngsters moving onto Hillview as the enemy within. John Mason, who became the first person to become a ‘licencee’ – shortlife tenant – on the estate in 1978, remembers the situation he met as “awful – total chaos”.

He added: “Many of the Huntley St squatters were affiliated to the International Marxist Group. So you got this burst of radicalism thrust into a working class area with a strong NF presence in it. It created a political maelstrom.” The NF went so far as to make a number of firebomb attempts on SCH’s Cromer St offices, destroying all its early records. But the worst incident came when an elderly Hillview resident was slashed across the face with a knife after answering the front door. “He was told, ‘we don’t want people like you here’,” remembers John. “Unfortunately, it was a case of mistaken identity as he was one of the council tenants still left on the estate.”

‘Despite its reputation, there were 700 people on the waiting list’ ©AKC 1980

In the summer of 1980, I reported on the murder of Pat Malone, a prostitute who operated from a squat in Cromer House that she shared with another woman and a man. Police said her body had been dismembered with a saw in the bath before being dumped in three plastic bags in Epping Forest.

It was the gruesome climax to an increasing number of frantic stories in the Journal about “Camden’s Dickens estate” over the past year, of running battles between the remaining tenants and glue sniffing punks, punks and skinheads, assorted gangsters and several police raids on brothels. To add insult to injury, this “rumbling volcano” and “festering sore” was also under attack from a plague of beetles.

Then in October 1979, the paper ran a lurid three-page feature by my colleague, Patrick Breen, headlined ‘The Hell-Holes of Hillview’. (Sadly, Patrick died suddenly in 2008 aged 50.) Alongside grainy looking images of the tenements, rubbish-strewn courtyards and frightened looking tenants, Patrick described his terrifying nights on this urban ghetto in miniature. One pensioner told him living there was “worse than the blitz”.

Later the national press got in on the act, with big spreads in the Guardian and New Society, the latter carrying an article by journalist and SCH licencee Eileen Fairweather who reckoned it was safer in war-torn Belfast. The press, councillors and local people all spoke as one – the sooner Hillview was demolished, the better.

Hillview regularly made the headlines in the Camden Journal

Yet, as SCH worker Martin McEntee pointed out to the Journal, there were 700 people on the waiting list wanting to move in. I was one of them and despite all the bad news about Hillview, I felt my luck had changed for the better when I was summoned to pick up the keys for no 88 Whidborne Buildings one of the estate’s five-storey blocks. Even so, I was unprepared for the scene of utter disarray that sprang to my eyes when I opened the front door. Although the furniture had been removed, there was junk everywhere. Worse still, there were splashes of blood on the walls and discarded needles on the floor.

“Everything alright then?” asked the man in a not very interested voice when I called round at the SCH offices on Cromer St.

“Er, the last tenant seemed to have left in a hurry. The place is a tip,” I said trying not to sound as though I was making a complaint. “What happened?”

“He never actually left the flat. He died there,” he replied in a matter of fact tone, flicking his long hair away from his face.

“What, was he ill or something?”

“Had a heart attack. In the bath. That’s where they found him. He wasn’t one of ours so I don’t know much about it.”

He tossed his hair back again and began busying himself with papers. Conversation over. If he wasn’t ‘one of ours’ who was he, then? I was a reporter and used to asking questions but on this occasion they stuck in my throat.

New look for courtyard entrances, 1983 ©AKC

I walked out a bit shaken, remembering how I had found the bath filled with a strange and sticky white substance – some sort of industrial disinfectant, I hoped. I wasn’t convinced about the heart attack story either.

Kicking up a fuss about the state of the place was a waste of time, even though it looked like a clear case for the health and safety executive. The rent was half the price of a council flat that I would have had no chance of qualifying for anyway. So donning a pair of Marigold gloves, I set about clearing up.

First stop was the bath. I scraped off the white stuff and threw loads of bleach into it, then cleaned the blood spots off the walls. Then I set about blitzing the rest of the flat, doorknobs and all. When I took up the threadbare carpets, I found a collection of credit cards covered with dust and carpet backing.

A few days later, I discovered that my predecessor was not only a drug addict and a thief but a pimp as well when a trail of young women began knocking on my door looking for him. “Is he in?” they would ask me with deadpan expressions as if I were his latest installation. “He’s gone,” I would say, affecting a similarly deadpan look.

After a few weeks, these late night visits eventually stopped and I quickly settled down. I got used to having to walk home via the B&B hotels cum brothels of Argyle Square, tailed either by kerb crawlers or police; I couldn’t make up my mind which was worse. I got used to young girls leading their wary looking clients up the stairwells to the brothels that still remained on Hillview; I got used to the variegated people who lived alongside me.

Why the estate was called Hillview, I had no idea. Perhaps its orignal Victorian residents had been able to see the distant hills of Hampstead Heath from the top floors. (The reason turned out to be very prosaic, I discovered many years later – Hillview was the name of an estate agent in Stamford Hill that handled its sale to Camden Council – see feature below.) But no matter, I really liked my new home. It was a one bedroom flat on the first floor, up a chilly flight of stone steps. The rooms were small but cosy and dry. The fireplaces had been bricked up and there was no heating, so I had to use Calor gas fires, which were an improvement on the paraffin heaters of my student days.

During the day, Whidborne Buildings was oddly quiet, devoid of even birdsong. You would not have thought you were living a stone’s throw away from the busy Euston Rd. Hillviewers tended to be nocturnal creatures, so nighttime was a different story. Noise seemed to bounce off the walls of the cramped courtyard and become amplified, so it was best to readjust your tolerance levels for the sake of personal equilibrium. All the blocks were arranged around narrow courtyards and this was another reason why the council thought they were unsuitable for modern-day living, given the density of the flats.

My immediate neighbour was a virtual recluse, his only companion a guitar, which I used to hear him play mournfully at all hours. When he did emerge, I would always recoil at his ghostly pallor and red-rimmed eyes; a bit like Andy Warhol. I once said hello but he seemed not to register my presence and moved silently on like a troubled spirit. The person opposite me couldn’t have been more different, an Eritrean sporting locks who always greeted me with a friendly smile.

Below me were a couple of blokes who played very loud rock music and, I guessed, were heavy drug users. Years later I would bump into one of them selling the Big Issue on Lamb’s Conduit St looking skeletally thin. I saw a flicker of recognition in his sunken eyes but said nothing. Opposite them, lived Zigay, another Eritrean, whose wedding party I remember spilling out of her flat and brightening up the otherwise gloomy courtyard. A nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, she had recently joined the small Eritrean community that had congregated in Hillview. At the time, Eritrea was engaged in an independence war with Ethiopia and many Eritrean students sent here to study on Ethiopian government scholarships soon felt unable to return home and applied for political asylum. As they had been living locally in student hostels, Hillview became a welcome refuge.

‘Dean’ (name changed) lived across the courtyard from me and was a regular visitor, always attired in an outfit bought from the nearby Laurence Corner army surplus store. An ex-Huntley St squatter and the brother of a well known black musician, he was an intelligent but edgy young man, given to angry outbursts. He would wax lyrical about his glory days down at the Huntley St squat and had plenty to say about the state of the world, so was interesting company if you had the energy to cope with the intensity of his outpourings.

Then one day I realised he had not been round for a while. After asking around I found out that he had tried to set his flat on fire and left Hillview. I never saw him again. Looking back, he was one of the many people living on the estate who might be classed as vulnerable. Most thrived on the seeming anarchy of the place and the warm embrace of being part of something, but a few didn’t survive.

Hillview gets a makeover

Saplings were planted in courtyards once dominated by bins ©AKC 1984

BY THE TIME I arrived on Hillview, almost all the original council tenants had been moved out and SCH now managed the entire estate on behalf of the council (although a few flats were let on the same basis by West Hampstead Housing Association). Together with the Hillview Residents Association (HRA), it continued to work hard to get rid of the criminals and close down the brothels and drug dens. Although some dodgy characters remained, most were more victims than villains who became part of the distinctive community that was beginning to take root.

Howard Hannah, the Journal’s news editor, told me to go and see ‘Becky’ (name changed) who also lived in Whidborne and was one of the resident leaders. She would be a useful source of stories, he said. I rang her bell and a tall man with de rigeur long hair answered the door. “I think you’ve got the wrong flat,” he announced before I’d even uttered a word. I am black and the same blank astonishment that someone of my complexion could ever be part of their world had occurred on a number of occasions.

“Is Becky in?” I asked patiently, thinking that my neighbours were not as progressive as they thought.

He looked at me puzzled for a moment, then turned round and shouted “Beckeeee”.

Becky, a small woman with glasses and similar length hair to her boyfriend, seemed surprised to see me as well.

I explained who I was, where I lived and where I worked. “If you need any publicity for the resident’s association, just pop round. I’m only two floors down,” I offered, thinking you can’t get much better than that. Becky was unimpressed, however. “Well, I usually talk to Howard,” she said blankly, her boyfriend still hovering in the background. Then in a more friendly voice: “But come along to some of our meetings. They’re open to everyone.”

SCH was very big on meetings. It was run as a cooperative and at first the normal divisions between landlord and tenant were not readily apparent. Residents were encouraged to become involved in running the estate and were employed to carry out maintenance and cleaning jobs. These were all well paid and contributed to the community ethos that was being fostered.

For those who did not get along to the regular tenants meetings, info about what was going on could be found in the monthly SCH News, which interspersed details of the organisation’s accounts and committee minutes with advice on how to prevent draughts and what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. The paper also gave information on current industrial disputes and ‘fight back’ campaigns. Another magazine, the irreverent Hillview Chronic, used to also drop through our letter boxes.

Rents included a membership levy to SCH, which helped boost the organisation’s finances. However, some tenants took advantage of the co-operative spirit and ran up huge arrears. Eventually, SCH was forced to become more business-like and insist on regular payment.

If the ghost of Charles Dickens had decided to haunt Hillview, it would have surely felt at home. Built by the pioneering East End Dwellings Company as homes for the poor between 1891 and 1910, the blocks had Victorian slum written all over them and, since the plan was to reduce them to rubble, they had been left to rot (for full history, see below).

SCH set to work giving the place a facelift, helped in the first few years by a generous £105,000 annual grant from the council. The brickwork on the stairwell walls was painted in an eccentric patchwork of colours, while rose pink and green were chosen to brighten up other parts of the estate. The desolate courtyards were planted with trees and shrubs and residents were encouraged to grow flowers in window boxes given away for free.

The rubbish bins were removed from the courtyards and into adjoining sheds. Cleaning and maintenance were regularly carried out. And individually, we all did our bit to regenerate the estate by turning our own flats into proper homes. But whatever anyone did, the dank and musty smell that I was aware of when I first visited the place persisted, as if trapped permanently in the walls. I was never able to put my finger on what it was and in my imagination thought of it as the accumulated smell of the hundreds of people who lived there over the decades.

One day I returned home from a weekend away to find my front door boarded up. In a panic I ran back out onto the street and saw that the windows of the flat above mine were burnt out. All I could see was black. I discovered later that a TV had blown up due to dodgy electrics, one of the hazards of living in shortlife housing. The ensuing blaze was so fierce, the Fire Brigade had to break into my flat to control it, consequently the front room looked as though it had been hit by a flood. Parts of the ceiling had collapsed and the walls were grey with smoke. I could have wept.

I spent the next two weeks in a B&B around the corner while the flat was redecorated. The hotel was one of many that lined Argyle St, one of the main drags in the King’s Cross red light district. Part of a terrace of Georgian houses, it looked quite nice from the outside but reverted to low budget as soon as you entered the lobby, all creaky stairs, thin carpets and stale food smells. “So young lady, what brings you here?” the proprietor, a small man who looked to be from somewhere in southern Europe, asked me as I booked in, looking me up and down.

I told him about the fire, and he gave a little smile, nodding his head vigorously. Then, thinking he may have got the wrong idea about me, I told him I was a journalist.

A look of alarm suddenly clouded his round face. “So who you work for?”

“Umm, I’m a freelance,” I replied, thinking it was better to keep it vague.

“So what you here for?”

“I told you, my flat got damaged in a fire.”

“Oh yes. Well, this is a good establishment,” he assured me. “Nothing to worry about here.” From then on, he eyed me suspiciously every time I went in and out the building.

The breakfast room was down in the basement and the only other people I ever saw eating there was a family from Malaysia. One morning, I commented to the hotelier’s plump wife, purely by way of polite conversation, that things looked quiet at the moment. “By the time you come down, they all gone,” she said with a nervous smile. “– How long you staying?”

I have no idea if this particular hotel doubled up as a brothel. All I know is, whenever I told people where I was staying, they would jokingly asked how business was. Of course, there was nothing funny about the scale of prostitution in King’s Cross and the way it blighted the lives of people living there. Its reach was wide. Beyond Argyle Square, it flourished in the lonely streets behind the station, where the Director of Public Prosecutions Allan Green was cautioned for kerb crawling in 1991, and along the bleak stretch of York Way.

Anxious and fed up, local residents held numerous meetings with the police who concentrated their efforts on pointlessly arresting prostitutes over and over again but seemed unable to catch the pimps or curb the menace of men propositioning women for sex, any women.

As Eileen Fairweather wrote in her New Society article of her experience of the short walk down Argyle St from Hillview to King’s Cross station, “The men with the law on their side… are still free to kerb crawl my neighbour’s 15-year-old daughter and my 53-year-old mum”, even though it was “obvious enough who the girls are, where they stand, how they stand”.

Newspaper reports claimed that many of the prostitutes had come down from the north of England out of fear of the Yorkshire Ripper who had begun his killing spree in 1975. Pat Malone, originally from Middlesbrough, is believed to have been one of them. Two months before her murder, a fire was said to have been deliberately started in her flat and she moved to another squat in Hastings House. Much to everyone’s alarm, the man arrested for her murder turned out to be a policeman. (PC Peter Swindell was later acquitted of her manslaughter but found guilty of dismembering her body.)

In 1982, a group of masked women occupied Holy Cross Church in Cromer St opposite the estate for 12 days to draw attention to police harassment of prostitutes. They were from the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), a group based at the King’s Cross Women’s Centre situated just a few yards away from my front window in Tonbridge St.

Despite its name, I suspect none of the women were prostitutes but the same radical feminists who belonged to other groups meeting at the centre, including Women Against Rape and Wages for Housework. Although their tiny two-roomed office was a part of the estate, they pointedly kept themselves to themselves.

At first they were very friendly towards me as I ticked all the right boxes – woman/black/ young – but the minute I wrote something about them they did not approve of they started to cut me dead in the street, which was quite often as I lived so close by.

The ECP ended its sit-in after the council’s women’s unit agreed to appoint a worker to monitor kerb crawling and police activity. Holy Cross’ normally amiable vicar, Trevor Richardson, was outraged that an “unrepresentative group of people” had used “bullying tactics” to achieve in days what King’s Cross residents associations had failed to achieve in years, despite countless meetings. He was also stung by accusations that he had let the women into his church. He told the Camden Journal, “I did not let them in but could not force them to go.”

The ECP may well have decided to target his church after he told the press on his appointment to the church a few months earlier, “Jesus Christ was a friend of prostitutes. If any needs help, I shall give it.”

We shall not be moved

THE MONTHS ROLLED into a year and I was beginning to regard Hillview as my home. So did all my neighbours and, having worked hard to bring the estate back from the brink, we felt less inclined to let go of it. So although the official talk was still about razing Hillview to the ground “once the money becomes available”, the seeds of rebellion were already taking root.

In 1982 the council had completed its refurbishment of two former Hillview blocks, Tonbridge and Hastings houses. They looked wonderfully pristine and were a testament to what the rest of Hillview could look like. Thus, the Save Hillview Campaign was launched with the same youthful energy that propelled the squatters movement and other manifestations of the new counter-culture. The first task was to win over the local community to the idea. Not easy, given the estate’s continued notoriety.

‘Tonbridge House looked wonderfully pristine’ ©AKC

Although police concentrated their efforts on closing down all the brothels following Pat Malone’s murder, two years later SCH News reported a “return of the bully boys”, but this time with guns. This was after gunfire was heard on the estate, the result of a turf war between different gangs. SCH had already made inroads into the immediate community via the Hillview Residents Association, which made a point of linking up with other King’s Cross tenants groups (although some of them refused to see shortlife licencees as proper tenants). This helped break down the us and them attitude and calmed tensions locally.

The area immediately around Hillview was depressingly shabby too, dominated by the Cromer St estate which, though built in 1951, was already looking the worse for wear. Even if Hillview vanished into thin air overnight, the red light district would still be there, apparently beyond police control. People felt betrayed by the authorities, says John Mason. “Once they were given a voice, the NF just melted away.”

Support came from the GLC (the now defunct Greater London Council) in the form of its St Pancras representative, Charlie Rossi, a larger than life character routinely described in the Journal as a “council rat catcher” on account of his job in the Town Hall’s pest control department. An Italian Scots with a fine baritone voice, his rendition of ‘Ave Maria’ at a pensioners’ tea party at the Holy Cross church organised by Hillview Residents Association brought tears to the eyes of many of the old folk attending. The parties began to be regularly held and soon moved on to the courtyard of the estate itself.

They were very successful in drawing the wider community into Hillview, as were the annual summer festivals, which by the 1990s enjoyed cult status, such was the unusual and varied entertainment on offer, most of it provided in-house. The early festivals, though, had been noisy, raucous affairs involving loud rock music and lots of free drink. After enduring one of them with my fingers plugged into my ears for much of the night and waking up to find the entire courtyard a sea of beer cans, I stayed at a friend’s the next time round. Organisers quickly found that this was not the best way to get locals onside, and Hillview festivals started to become family-friendly, known for their wacky conviviality.

When it came to winning over the council, we found ourselves up against a brick wall. Councillors were adamant that Hillview Should Go and one of the fiercest advocates of this was King’s Cross representative Barbara Hughes, who had little time for shortlifers, dismissing us as a bunch of mouthy middle class opportunists. The council’s new housing chair, Julian Fulbrook, was also in no mood for compromise. In 1980 he had told the Journal, “I would like shortlife residents thrown out by the scruff of their necks.” And he still seemed to feel the same way.

All the fun of the festival, 1991 ©AKC

It was true, shortlifers were not your usual type of tenant. Young and articulate and with plenty of campaigning experience behind us, the council soon discovered it had a formidable adversary on its doorstep. The chair of the Hillview Resident’s Association was a fiercely intelligent New Zealand woman called Verna Smith. I understand she went on to become a government minister back home. If that’s true, I am not surprised. At a public meeting attended by Cllr Hughes and her Labour colleagues, she forcefully argued that demolition would create “a vast hole” in the community SCH had built up over the years, the last thing a troubled area like King’s Cross needed. But what really got up councillors’ noses was her insistence that they had a moral obligation to allow residents to stay on the estate. Firstly, she argued, they had been living in shortlife accommodation for much longer than anyone had expected, and secondly they had cleaned the estate up, something the council and the police between them had been unable to do.

In a way, Verna was a prime example of what the council held against us. She was “young, middle class and mobile” – a phrase Fulbrook coined to describe us. The implication was that we were not really desperate for somewhere to live, unlike the thousands on the housing waiting list. Councillors accused us of wanting to “jump the queue”, that is, to get permanent housing without being on the waiting list. The fact is, we were in a Catch 22 situation. We did not qualify for a place on the waiting list because we were not homeless. Yet, we had no security of tenure, meaning we constantly lived under the threat of homelessness.

Of course it was true, some shortlifers were from well-to-do homes and were “slumming it” as a kind of rite of passage. Others would have easily been able to find somewhere to live if pushed. Still more were just passing through, like Verna herself. For the most part though, our comparative youth meant we did not have the resources to set up home elsewhere even if we wanted to. Moreover, the majority of us were no longer wild young things of the council’s imagination. A survey carried out by SCH in 1984 found that the average age on the estate was now 28. A logical consequence of this was that many tenants had begun to settle down and have children, so deepening their stake in the immediate community.

Needles collection, as shown in Chris Reeves’ Save Hillview campaign film

Small kids soon had the run of Whidborne but especially Midhope courtyard, watched over by a network of carers – mostly first time mums delighting in their alternative sisterhood. “These are all my daughter’s brothers and sisters,” one told me with a dreamy look as her child played happily with the neighbours’ children. It was an idyllic picture, one that contrasted with the grim reality of King’s Cross, symbolised by the used condoms and needles littering the streets. But simply by existing, surviving and thriving, Hillview gave people some kind of hope for the future.

Apart from our own housing concerns, Save Hillview was also a reaction against the still enduring fashion for smash and rebuild which had already laid waste to parts of the borough, particularly West Kentish Town, where SCH managed a number of street properties. There, anonymous council estates had replaced rows of fine Victorians housing whose only offence was that they were a bit run down or lacked a bathroom. Communities around Queen’s Crescent had had the heart ripped out of them, with all the consequent social problems that persist today. Needless to say, the houses that escaped the bulldozers are highly sought after.

A terrible example of municipal vandalism closer to home was Tolmer’s Square, a charming but decaying enclave of Victorian houses just behind Euston Rd that had become the centre of an epic 17-year battle between tenants and property developers who wanted to replace the whole lot with offices.

In what appeared to be a sensational victory for residents, Camden Council purchased the land in 1973. But within a few years it performed a U-turn, demolishing the houses to make way for a horrible office block of mirrored glass and a small estate of pokey-looking red brick flats. This signalled the latest infiltration of office development on the north side of Euston Road, once a preserve of working class housing and even a thriving market until the Euston Centre complex reared its ugly head in the 1960s.

The recently completed Regent’s Place has moved the process a stage further and, if the HS2 train link goes ahead, the entire area around Euston Station will become a forest of steel and glass. Already, council blocks on the Regent’s Park Estate are being sized up for demolition and Drummond St, famous for its Indian eateries, faces annihilation.

Tolmers Square was another famous squat of the day and I was sent down to cover the inevitable eviction in May 1979. The 50 or so squatters put up little resistance and it was over very quickly. But I remember them standing forlornly around the piles of their belongings that had been dumped in the middle of the square not knowing where to go. Many of them ended up in Hillview and, like their Huntley St comrades, regarded it as their next battlefield.

In 1986, SCH and HRA commissioned a report by Camden Town-based architects Hunt Thompson to argue the case for the estate’s renovation. This included a detailed survey of the blocks and Hunt Thompson’s own refurbishment plan, which it linked to the area’s regeneration. This won the support of Prince Charles, who was establishing himself as a champion of heritage architecture.

But councillors stuck to their guns and the following year cut the Town Hall’s subsidy to SCH, awarded to meet the shortfall from the lower shortlife rents. However, two things were staying the council’s hand – lack of immediate cash because of government cutbacks, and 400 tenants who weren’t going to leave the premises quietly when told to do so. In 1991 during the run up to the local elections, a group of residents delivered a body blow to the demolition plans when, as members of the King’s Cross Ward Labour party, they de-selected Cllr Barbara Hughes and Tony Dykes, then Labour Group leader. Both were replaced by councillors more sympathetic to the cause, Gloria Lazenby and John White.

Court in action

SCH MANAGED SEVERAL other shortlife blocks in the area. One of them was Gray’s Inn Buildings, up the road from King’s Cross on the fringes of Clerkenwell. Gray’s Inn may have shared the name of the nearby legal chambers but had none of its genteel elegance. Built in the 1880s, it was a somewhat forbidding red-bricked mansion block overlooking an unlovely stretch of Rosebery Avenue. It flanked a narrow courtyard that always seemed bleak, even in summer.

Gray’s Inn had an even worse reputation than Hillview for drugs and violence and on New Year’s Eve in 1983 two drug dealers were murdered there. Once people began to have kids they would move out, leaving mainly single people behind. They included some of SCH’s most militant members and in 1985, when Camden tried to take half of the estate back for redevelopment, Gray’s Inn residents legally challenged the evictions, arguing that they had security of tenure.

Hillview OAP party, a scene from Chris Reeves’ 1993 film

Following a landmark ruling in favour of the applicants, the case was adjourned for further clarification. The law is an ass and in 1992 the High Court swung in the opposite direction in support of Camden.

Yet there were signs that the council was beginning to soften its stance on shortlifers. In Chris Reeves’ 1993 film about the estate, Hillview is not a problem, it is a solution, town hall housing chair, John Mills, acknowledged that the shortlife movement in Camden had made “a substantial contribution”, not only looking after once derelict property but also “producing stable communities”. He added: “We are also mindful of the fact that if people have lived somewhere for 10 years that really is a bit of a different situation then if they’ve lived there for six months.”

Reeves, who lived on the estate, made the 20-minute film as part of the Save Hillview Campaign, inter-cutting interviews with earnest tenants and shots of bright and verdant courtyards with footage from around King’s Cross station, the drugs, the sex trade and the lost souls, a bit like scenes from the movie Mona Lisa except that this was the real thing.

Cath Packard, who lived on Midhope with her partner and two small daughters, admitted she avoided going towards King’s Cross late at night because it felt increasingly unsafe. “But even though it is probably more violent now than I have ever seen it I feel quite secure on the estate.”

Her neighbour, Ann Demspey, agreed, pointing out the wider implications of this: “We’re a kind of barrier, a buffer zone between [the King’s Cross frontline] and the community as far back as Holborn. If that barrier is strong then it must mean that life is a better quality for the people who live beyond. But if our estate were to go down then it would be very bad news for people living further south.”

The film paints an affectionate picture of a settled and self-sufficient community who love living on the estate and express real pride in being part of its amazing transformation.

“Compared to council estates, there is much less violence here, much more social input from residents and this must be because people have control over their lives here,” said Makonnen Tesfaye, another Midhope resident. “If this situation is replaced by formal council management, such personal initiatives that drive [SCH] members would be lost and I’m afraid bad things could start happening.”

Locals attending Hillview’s annual pensioners party were unanimous in their praise of shortlifers. “They are absolutely fabulous and should be allowed to stay,” said one.

While Hillview’s future remained uncertain in the light of the court case, Hillview residents leader Lorna Whitehorn was optimistic that councillors could be “educated” into seeing sense. And so it eventually proved. Instead of pressing ahead with the evictions at Gray’s Inn Buildings, the council decided to throw in the towel. Weakened financially and politically by the onslaught of the Thatcher government and aware that carrying out mass evictions was politically unacceptable it entered into negotiations with SCH over the future of both Gray’s Inn and Hillview. This resulted in Hillview’s proposed sale for £1.4 million to Community Housing Association (CHA), with SCH playing piggy in the middle.

Midhope House overlooking Whidborne St, 2011 ©AKC

SCH was determined to get the best deal possible for residents. The easy bit was making sure that Hillview ended up being refurbished. CHA had enough savvy to know that the coming of the British Library just over the road (it was to finally open in 1997) marked the first step in King’s Cross’ overall regeneration. It clearly viewed Hillview as a landmark project in its ever-increasing portfolio. The hard bit was securing permanent accommodation for tenants, either back on the estate for those who wanted to stay, or in equivalent accommodation elsewhere in the borough.

Although the council had a legal obligation to re-house families, it wanted to have the final say in where they should end up – the top floor of a tower block came immediately to mind. But SCH had a tough negotiating team with as much know-how as the officials on the opposing side. In 1994, after a year of talks, our team came away with what they called the “best deal possible”. Only those who had lived on the estate for less than five years failed to get permanent tenancies. Instead, they would continue their shortlife existence elsewhere, most often in Gray’s Inn Buildings.

Gathering Whidborne courtyard, 2009, showing my former kitchen and bedroom on the first floor ©AKC

Naturally there were cries of sell-out from those who wished to remain independent, but the days when the council might consider options like housing co-ops, such as the one in Carol St, Camden Town, were long gone. Most Hillviewers, having lived in limbo on the estate for more than a decade, merely breathed a sigh of relief that it was all over. For me though it wasn’t. Several years earlier, following the birth of my daughter in 1987, I had moved out of Hillview and into a maisonette in one of the houses SCH managed nearby. The street properties were not part of the deal but residents monitored events from there closely, knowing that it would soon be our turn to argue our case.

Over the next year or so, Hillview tenants were gradually moved off the estate and into temporary accommodation while the builders moved in. To my surprise, quite a few people who only a few years earlier professed their undying love for Hillview chose not to return and headed for the wilds of Kentish Town and Camden Town.

Midhope courtyard, Sept 2016 ©AKC

For those who chose to stay, it has probably been well worth the struggle. They have seen their once notorious estate beautifully restored and a plaque on the estate acknowledges the role of Hillview Resident’s Association.

But its sale to a conventional housing association with a reputation for its hard-nosed attitude to tenants marked the end of an era. Although it was initially conciliatory, for example supporting the courtyard planting and helping to fund the Hillview Festival, CHA was determined to undermine the Hillview Residents Association and SCH, which had both proved such a formidable force. One of its first acts was to move SCH out of its Cromer St offices and then to poach some of its staff.

Not for the first time in my life did I become astonished at people’s duplicity as former SCH stalwarts became CHA lackeys and proceeded to give residents grief. Later, CHA appropriated the levy on rents used to finance tenant activity and did all it could to destroy any vestige of SCH’s democratic system of housing management.

Nevertheless Hillview’s second coming is testament to SCH’s remarkable achievements. Firstly, it transformed a feared criminal ghetto into proper homes for people through the active participation of residents; secondly, it overcame the hostility of the wider community by becoming part of it; thirdly, it took on the council and saved fine Victorian buildings from demolition; last but not least it secured permanent housing for the majority of its members.

So although the word shortlife is meaningless today and SCH is itself a distant memory, the struggles of its tenants for decent housing in decent communities certainly deserve their place in history.

The original Hillview shortlifers still try to keep things going with the old SCH spirit but the place will never be the same again. The Hillview Festivals gradually lost their sparkle and became quite subdued affairs, more happy reunions and a reminder of the anything-goes kind of sprit. They have now fizzled out altogether.

Whenever I visit the estate though, it is always with a great sense of nostalgia and astonishment at its transformation. Midhope House even has water fountains amidst its exuberant courtyard foliage, a million miles away from the overflowing rubbish bins that I walked quickly past on my very first visit.

© Angela Cobbinah, July 2012; updated April 2014

A history: from slums to model dwellings and back again

Original plaque, Kellet House ©AKC

IT MUST HAVE been with great pride that Edward Bond, chair of the East End Dwellings Company, announced the acquisition of “an important property” to his fellow directors in 1891. [Eigth Ordinary General Meeting, East End Dwellings Company, 16 February, 1891].

A stone’s throw from King’s Cross and St Pancras stations, it signalled the company’s expanding housing portfolio that began in its Whitechapel heartland and was now spreading ambitiously westwards.

The latest purchase comprised seven acres of land and fitted in perfectly with the company’s philanthropic vision of providing “model dwellings” for London’s poor. It was presently inhabited, directors were told, “by a disreputable class of tenants” who lived in “very neglected and dilapidated conditions”. Here was chance to uplift them.

Argyle Walk, 2015. This was the most run down part of the Lucas Estate before East End Dwellings’ intervention ©AKC

By 1893 the slums had all been cleared to make way for the new Cromer Street Estate, which boasted a mix of different sized flats, mostly with shared sinks and toilets, but a few that were self-contained. A resident caretaker, communal laundries, a workshop and a club room were among the facilities provided.

The estate was a departure from the EEDC’s earlier blocks in the East End, which tended to be spartan and consisted mainly of single room accommodation aimed at the very poor. It was hoped that mixed value rentals would create better communities.

In 1894, the directors noted with satisfaction that “not a single tenement was unlet” on the new estate and that more than 1,200 people lived there. In fact, Cromer Street would be the EEDC’s biggest concern and most successful in terms of the revenue generated. The separate sections of the estate – Tankerton and Loxham houses and Whidborne Buildings (1891), Lucas and Ferris houses, Midhope Buildings and Cromer House (1892), and Charlwood and Kellet houses (1893) – were situated on the former Lucas Estate, which had been acquired by Joseph Lucas towards the end of the 18th century as farmland. He began to develop it for terraced housing, making Cromer St (until 1834, Lucas St) its main thoroughfare, after the town in Norfolk his family hailed from.

But the building of the Regent Canal in 1820 and later the railways at King’s Cross and St Pancras brought in thousands of labourers and displaced as many residents. Overcrowding and squalor became rife, with whole families living in one room. Prostitution and drunkenness were also said to be widespread. In 1883, a report of a visit to the Cromer St area by Mr N Robinson, chair of the district sanitary committee, said: “We have visited a place called Coopers Buildings. In the interest of common decency as well as of public health, the sooner the dreadful double row of little houses was levelled with the earth, the better it would be” [As quoted by the Hillview Chronic, 1980]

Midhope St, 2016, with back of Argyle Square houses in the foreground ©AKC

This reflected the growing housing crisis afflicting poorer areas of London, where people were forced to rent privately from a limited stock. In tandem with several other charitable organisations, the EEDC was set up in 1884 to provide homes for the working classes that returned a small dividend to its shareholders – hence the term ‘five per cent philanthropy’.

At the time, the state’s involvement in housing provision was limited to government grants awarded to bodies like the EEDC and slum clearance schemes to provide access for new dwellings, a move prompted by increasing public anxiety about the spread of disease and vice due to squalid living conditions. In London, the first municipally-built homes did not appear until 1900 in the form of the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch.

The founders of the EEDC, social reformers Rev Samuel Barnett, vicar of St Jude’s in Whitechapel, and Octavia Hill, combined Christian ethics with paternalistic housing management in which tenants were actively encouraged to lead responsible and respectable lives. It was Bond, a Hampstead barrister and close friend of Octavia Hill, who oversaw the business of the EEDC for the next 37 years. When he died in 1920 the chair was taken over by his brother-in-law Alfred Hoare, a banker who, as a founder director, had attended the 1891 meeting. He held the post until 1925. This longevity of office ensured at least consistency of purpose.

It was Bond and co who insisted the street names of the former Lucas Estate be changed in order to “obliterate the unpleasant associations” of the area. For example, Dutton Street, the location of the worst of the slums and site of a ‘ragged school’, was renamed after Tankerton in Kent, where the EEDC had property, while Brighton Street became Whidborne, after Ferris Whidborne, a former curate of St Pancras Church who was related to the Lucas family.

The new estate brought immediate improvements. In Charles Booth’s poverty map of 1899, the area was re-coloured from the black of a decade earlier – the worst designation – to purple, meaning a mixed population of both the “comfortable” and “poor”, noting that occupants now included policemen and postmen.

In 1904 and 1910, the EEDC added two more blocks to its Cromer St development, Tonbridge and Hasting houses respectively. The flats were aimed at a better class of tenant, being self-contained with their own kitchens and toilets and completely enclosed internal staircases.

By this time the company was on a roll. In addition to its several estates in the East End, it had also built model dwellings in Barnsbury and in the Caledonian and Pentonville roads area. Following a lull in its homes programme, the company decided to extend its Cromer St frontage in the 1930s by building three modest four-storey flats, one of them named after Edward Bond. The other two were Moatlands and Whiteheather houses. In 1949, Loxham House, which had been destroyed during the Blitz, was rebuilt at the back of Edward Bond House.

But the area had once again acquired a tough reputation. Victor Gregg grew up in King’s Cross between the wars, attending the Cromer Street School, the roughest of the neighbourhood’s three senior boys schools. “The streets surrounding this establishment were completely run down,” he writes in his memoir King’s Cross Kid. “The people who lived there could hardly be blamed for giving up hope, and yet there was a never-say-die spirit of survival.” [King’s Cross Kid: A London Childhood Between The Wars by Victor Gregg with Vic Stroud, published by Bloomsbury, 2013]

The book reveals that post code wars are not a modern-day phenomenon – street gangs were common in the area, even among primary school children, and those who strayed outside their domain, that is, walk round the wrong corner, could expect trouble: “Kids from the same street regarded each other as […] all part of a family. Three or more boys entering a strange street immediately became subjects of suspicion and more often than not they were challenged.” Gregg matter-of-factly describes several bloody encounters and how, despite the efforts of the recently opened Tonbridge Club on the corner of Cromer St and Judd St where boxing was taught, boys tended to ignore the Queensbury rules. “Unfortunately, [they] came from streets where there was only one rule – give no quarter,” he writes.

The Cromer Street Estate itself fell into a slow decline, its tenement blocks blackened by the London smog and damaged in parts by Hitler’s bombs. It certainly did not compare favourably with the modern housing schemes being built by the local authorities. An article in the parish magazine looking back at life in the area in the 1930s, reads: “In the buildings [on the Cromer St Estate] the only hot water was boiled on the gas stove. Lavatories and sinks were on landings shared by as many as four families.” [‘Nostalgia’ by J Woolham, Holy Cross Parish Magazine, September 14, 1980]

Even in the better quality Tonbridge and Hastings houses, which provided baths in individual flats, the baths were not plumbed in but part of the kitchen with removable wooden tops that served as a table or working surface.

Whidborne St, 2015, little changed over the last century ©AKC

Tenants also complained of lax maintenance. In 1939, just before the outbreak of war, The St Pancras Gazette reported the threat of a rent strike because of poor conditions on the estate. A few months earlier tenants had petitioned the EEDC for a sink to be provided in each flat, repairs and decorations to be regularly carried out and “adequate lavatory accommodation” to be provided. However, it was to no avail. In her 1980s study of the Cromer Street Estate, Judith Martin points out that flats in drawings prepared in 1963 were unchanged since 1891: “Many had one room dwellings, coal ranges and no indoor lavatories.” [East End Dwellings and the Cromer St Estate]

Jessica Mackenzie was born on the estate. She told a local history project in 2006: “My mother and I lived from 1923 to 1930 in one room in Whidborne Buildings, which was just a room. In it we had a double bed, a kitchen table, four chairs, a dresser, a coal box and a cooker. That was it. There was no bathroom and no water on the premises at all.” [DVD, Argyle Sound Trail, King’s Cross Oral History Project, 2006]

With all the pioneer directors now long gone, the EEDC began to behave less philanthropically, regularly complaining during the 1940s about tenants who’d died leaving rent arrears, and describing borough sanitary chiefs’ complaints about inadequate food storage cupboards in Whidborne Buildings as “unjustifiable pressure”. [East End Dwelling Company, directors’ minutes, December 1948]

In the end, it was legally forced to take action, alongside repairing defective sinks and carrying out redecoration works. By 1955, faced with crumbling Victorian buildings, it finally broke free of its charitable roots and turned itself into a speculative property developer under the new name of Charlwood Properties. This later became part of Town & City Properties Ltd.

Although the estate suffered continued neglect, residents did their best to keep up appearances. Kim Winterton, who lived in Midhope House as a child in 1956, remembers the concrete stairs being scrubbed with Vim every morning and front steps being painted bright red on a regular basis. She told me: “Wash day included a huge mangle squeezing the excess water out of bed sheets washed by hand and then hung on the washing lines that straddled the buildings. If your whites were a bit grey you daren’t hang them out – so much pride!”

Barbara Hughes, who would later represent King’s Cross ward on the council, brought up her three children on the estate and remembers it with fondness despite its rundown condition. “In 1954 my husband got a job as a caretaker, which came with a flat in Whidborne Buildings,” she told me. “It was a long way up on the fifth floor with a shared toilet on the landing and no bathroom, just a tin bath. But it wasn’t a bad flat and we were lucky because we had hot water.”

The family later moved to a three-bedroom flat on Midhope. “It was in the part that had got bombed in the war and had been rebuilt to have self-contained flats, so it was wonderful. It was also on the ground floor, which saved climbing all those stairs. By this time, we knew almost everyone who lived on the estate and it was a very friendly place to live.”

The fly in the ointment was EEDC’s reincarnation as Charlwood Properties. “They were really poor landlords,” remembers Barbara. “They did not bother about maintaining the place and things just went downhill. Towards the end of the sixties, there were rumours that Charlwood wanted to sell off the estate. Then a company official, who we called Mr Faust, kept threatening tenants that they would soon have to find somewhere else to live. We were furious about this and we began to get organised.”

When Cromer Street was finally placed in the hands of Hillview Estate Agents of Stamford Hill in 1972, 300 tenants signed a petition calling on Camden Council to add the estate to the private properties it was busily buying up at the time, and, if talks broke down, to compulsorily purchase it.

This proved unnecessary. Two years later, following successful negotiations, town hall chiefs announced that the Cromer Street Estate had been bought for £1,7m. The freehold, plus the leasehold of Hastings House that was due to expire in 2007, comprised 450 flats, 22 shops and garages and storage units. This represented a substantial increase in the town hall’s housing portfolio, it was noted. [Minutes, full council meeting, January 1974]

In memory of Edward Bond ©AKC

“These people […] are living in slum and semi-slum conditions and have really suffered,” Cllr Joe Jacobs was quoted in the Hampstead and Highgate Express as saying afterwards. Homes that had been built some 80 years earlier to replace slums had gone full circle, only now, by some quirk of fate, they were to be known as Hillview after the estate agent’s that handled its sale. (The name Cromer Street Estate was passed on to a collection of post-war housing blocks nearby.)

Camden’s plan to modernise the estate quickly receded in the face of the enormity of the task before it. Not only was it running out of money but, Argyle Square, which until the ‘50s had managed to remain respectable and effectively off limits to the riff-raff around Cromer Street, was now at the heart of the King’s Cross red light district, which saw Hillview as a convenient extension of its activities.

By 1978 the council was proposing instead a £4-5m redevelopment scheme that would replace Hillview’s high density accommodation with up to 50 family-sized houses with gardens.

“I believe that our plans for this estate will go a long way towards uplifting the tone of the area,” Tony Craig, one of the local ward councillors, told the Camden Journal that October. “King’s Cross has long been a squalid red light area and the existence of some of the worst slums in the borough near the main rail termini has done little to prevent general degeneration of the area. I hope the new estate will be free of these problems.”

All the Victorian blocks were to be knocked down while Tonbridge and Hasting houses were to be refurbished. Flats deemed unfit for family occupation would be handed over to Shorthlife Community Housing (SCH) as temporary accommodation. This would also prevent squatting, which had become another of the estate’s problems as council tenants were moved out.

Barbara Hughes was now living in Tonbridge House, which had become overrun with squatters. Never one to suffer fools gladly, she sprang into action: ‘There was a group of them with brightly coloured hair – punks I suppose – who would actually advertise these all night raves that people had to pay to get into. After one particularly bad night I went upstairs and gave them what-for. They left soon afterwards.”

By the following year, with the scheduled demolition still stalled and the estate falling further into disrepair and disrepute, the Camden Journal joined in the local outcry against council dithering, pointing to the irony of its just opened £7.5m town hall extension and “the rot” that lay directly behind it.

“We are talking about the Hillview Estate just yards from your offices,” it stormed in a front page open letter to housing chair Ken Livingstone. “Go and see for yourself. Perhaps then you will see there is only one solution. You need to act now and PULL THE BLOODY LOT DOWN.” [‘An open letter to the council’, Camden Journal, October 1979]

At the time, few of the 130 or so shortlife licencees – renters – living on the estate opposed demolition such were the enormity of the problems they had to put up with, summed up by one of them in SCH News as “blocked drains, leaky roofs, outside loos, pimping, pests, drugs and violence”. For the most part they were more concerned about their prospects of being rehoused in the event of the blocks going. As single people they had the lowest priority on the waiting list.

As for SCH’s own position on Hillview’s future, this was non-commital, as expressed by one of its officials, Martin McEntee. “As far as we are concerned we are here to make use of the flats,” he told the Journal flatly. “We are not here to manage them.”

In the febrile atmosphere surrounding Hillview, any mention of its architectural merits was considered perverse, while its pioneering role in the history of social housing was either not known or completely ignored.

Within a few years all this would change. SCH licencees, caught in the limbo of repeatedly postponed demolition plans, decided to combine a campaign for their own rehousing with that of the estate’s total refurbishment. Almost a century on, the ghosts of the East End Dwellings Company pioneers continued to wander.

© Angela Cobbinah, May 2016

From squatter to housing co-op founder

Les outside one of the co-op’s houses

In his long arc through life, Les Coupland-Eve has gone from squatter and short life licensee to co-founder of a housing co-op whose property portfolio began with run down houses he might have once squatted.

I first met him in the 1980s when he did a repair job in my flat on the Hillview estate while working for Shortlife Community Housing (SCH), looking much the same as he does now, and as cheerful as ever. At the time, he was doing the rounds of short life accommodation, having been one of the 150 squatters evicted en masse from Huntley St in 1978.

“Most of us were rehoused in Hillview after a deal between SCH and Camden Council, but I wound up squatting an empty property in Fitzroy Square that used to be a hostel,” he recalls. “About 50 of us lived there. It was massive and very grand – even the bathrooms had 15ft ceilings. We were basically waiting to be given short life housing and we called it Huntley St in Limbo.”

Within a few months he was allocated an SCH flat in Gray’s Inn Buildings, a mansion block on the corner of Rosebery Avenue and Clerkenwell Rd that had seen better days, and it was through SCH that he also got a job as a maintenance worker on Hillview, mainly doing carpentry.

Originally from Redcar in the northeast of England, Les was one of the thousands of young people who joined the squatting movement during its 1970s heyday, as much a way of getting a roof over his head as being part of a blossoming counter-culture.

He arrived in London in 1976, having already packed a great deal into his teenage years, apprenticing as a carpenter before going on to work in Teeside steel plants, where the pay was better, and from there embarking on some travel, then sweating it out in a hotel kitchen in Folkstone, Kent. It was inevitable that the university of life would eventually draw him to the capital.

“I didn’t have a job or somewhere to live lined up or anything, but as soon as I got off the train at King’s Cross I met people in a similar position and linked up with them,” he says. “I had heard about the squatting movement and took it from there.”

He ended up in a squat in Portnall Road, Maida Vale, just around the corner from Elgin Avenue, where a long-running battle between 200 squatters occupying a row of houses owned by the Greater London Council had drawn to a successful close, with everyone being granted permanent or short life accommodation.

Les was in his element: “I saw myself as an anarchist. I believed in the power of the collective, and still do, how people can take control of their lives without bosses breathing down their necks.” Moreover, he had a great deal to contribute: “I was a carpenter and a locksmith and would help people get into empty buildings, then I would help make them habitable. Let’s say l was very useful,” he smiles.

Next stop was Huntley St in Bloomsbury, where the occupation of 54 empty police flats had begun in February 1977. It was another high point of the counter-culture that combined solving homelessness with direct action and a new way of living.

“There was so much going on, it was fantastic,” enthuses Les, who helped run the squat’s wholefood cafe. “I really loved the camaraderie. My parents weren’t that great and I didn’t have an easy childhood. Squatting offered me the family I never had.”

Frequently to be seen darting about the streets on his bike, Les is taking a break to talk to me at a cafe round the corner from where he lives in Camden Town, wearing his trademark beanie and adorned with a profusion of bracelets and necklaces. He becomes momentarily still as the vivid memories of the day of eviction pour out: “While we were building barricades to keep the police out, two people, ‘Nigel’ and ‘Mary’, came along saying they were homeless and wanted to join in. Some of us were suspicious because they were a bit nosey and kept asking a lot of questions. We were right – it turned out they were police spies.

“Very early one morning, far too early to be out and about, we caught them trying to leave the building. It was obvious they were trying to get away. Soon afterwards, the eviction began. It was para-military operation with 650 police, helicopters circling above and bulldozers. The police had all been trained in Germany especially for the job. That’s how big it was. It was really over the top. We had gotten most people out by then and there were only about 14 of us manning the barricades. Eleven people were arrested for ‘resisting the sheriff’.”

They included Piers Corbyn, one of the squat’s leaders, who had poured a bucket of water over the sheriff’s head.

Gray’s Inn Buildings, July 2021

At Gray’s Inn Buildings Les’ culinary skills were put to good use in the Love and Crumbs cafe, which was based in a top floor flat, complementing a food co-op he was involved in on the ground floor. Healthy eating was a key part of the alternative society being nutured. Provisions were sourced from Community Foods in Tolmers Square, where another squat was in action, and Alara, a still thriving business that started out in one of the shop fronts on the Hillview Estate. “The meals we made were strictly vegetarian, things like nut roasts, soups, curries and salads, and prepared as much as possible with organic ingredients. It has all become very trendy now but we were doing it yonks ago.”

It was a heady few years. In between learning furniture-making and new building skills at college, Les held down a day job and did voluntary work with young addicts. As a latter day eco-warrior, he made several trips to Ireland where he campaigned to keep dolphins safe from fishing nets, and also spent a year in Nicaragua doing volunteer building work for the revolutionary Sandinista government, a destination many radically-minded youngsters headed for. Music was his other love and, in a nod to his Irish and Welsh ancestry, he learned to play the bodhran drum and now performs in pubs and community festival as a member of the Northern Celts folk group.

He remembers Gray’s Inn Buildings with affection. “All sorts went on there,” he says with a laugh without elaborating. His six-year stretch there ended with a move to a number of SCH street properties around Kentish Town and Camden Town. The last of these was an imposing four-storey Victorian house in Stratford Villas near Camden Square.

“At the time in Hillview there was lot of talk about forming a housing co-op, but for various reasons it never went much further than that. Some of us got to thinking that we could set one up one elsewhere, but on a smaller scale.”

The Stratford Villas house seemed a good place to start, especially as there was a derelict property next door to it, seemingly all but abandoned. Over the next two years or so Les and 10 other short lifers set about drawing up a funding application to the government’s Housing Corporation to buy up and refurbish the two houses and several others they came across, including one in Mansfield Rd, Gospel Oak.

“Our aim was to house single people, something that the Housing Corporation wanted to make some sort of input to as they realised there was a gap in provision. They granted us interest-free mortgages and we were able to commission a firm of architects, Solon.”

The South Camden Housing Co-op was formally launched in 1991 and now has 15 properties and 40 members living in parts of Camden borough estate agents today salivate over. Accommodation ranges from one- to four-bedroom flats offered at social rents, around £110 a week for a two-bed including service charges. The passage of time means that some of the pioneers of the scheme have now sprouted families and one of Les’ three children, having grown up in Stratford Villas, has just become one of the co-op’s latest new tenants. A house in Leighton Road, Kentish Town, is also rented out to an organisation providing homes for people with learning disabilities.

The co-op employs two people, a maintenance worker and administrator, while Les serves as chair, running the business with the help of an eight-strong management committee. At the moment, in response to the ever spiralling housing crisis, South Camden is exploring the possibility of purchasing another property locally.

“I am very proud of what we have achieved as a co-op,” says Les. “We came from squatting and the campaign for housing for all. We now manage our own housing without any greedy landlord getting in the way. To me it is a no brainer.”

© Angela Cobbinah, June, 2021

Save Hillview – Cllr Hughes looks back

When I interviewed Barbara Hughes in her cosy flat in Queen’s Crescent more than 30 years after she had locked horns with the Save Hillview campaign, it was clear she had lost none of her fighting spirit.

Although in her eighties and long retired from formal politics, the former mayor of Camden remains active with forthright views on all manner of subjects.

Barbara has deep roots in King’s Cross, having brought up her three sons on the Hillview Estate in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Barbara Hughes, 2015 ©AKC

She was a big voice in the campaign to get Camden Council to purchase the blocks and then went on to become the local ward councillor just as Save Hillview was gathering steam in the early ‘80s. Therefore, when she spoke on the matter she did so with a certain passion.

Looking back, it was not so much Hillview’s demolition or otherwise that exercised her so much as the demand of its shortlife tenants for permanent housing. “I didn’t feel the council should change its letting policy just because a group of people had clout,” she told me. “It was also obvious many of the shortlife tenants were well off and didn’t need council housing – they were just jumping onto the bandwagon.”

In 1991 Hillview residents demonstrated their clout by joining the Labour party and getting her and fellow ward councillor and Labour leader Tony Dykes deselected. “I was gutted but that’s politics for you,” she says, pointing out with some satisfaction that she easily won the seat back four years later.

At the time, there were rumours that Barbara wanted Hillview pulled down because she had hated living there. This turned out to be far from the truth. “I was never against it being refurbished,” she said. “I used to live on the estate and have happy memories of it. But as a local councillor we represented the whole community and had to listen to those who wanted to demolish the estate as well.”

Away from acrimonious meetings and newspaper reports of tug-of-war battles between shortlifers and the council, it was clear that there was also plenty of behind- the-scenes co-operation: “I had a lot of time for some of the shortlife leaders, people like Sheila Kelly. They were really good and we worked successfully together on issues like the kerb crawling and drug problems, which we all wanted to end.”

Barbara also acknowledged that the repeatedly delayed demolition of Hillview strengthened the shortlife case for rehousing. ‘It’s clear the longer things took the more settled people would become. In the end, many were entitled to be rehoused anyway because they had become families.’

As for Hillview today it looks very nice, she said: “They did a wonderful job with the refurbishment and I have no regrets on that score.”

© Angela Cobbinah, May 2016

Restoration drama

The following is part of my contribution to the King’s Cross Story Palace, a two-year Heritage Lottery-funded project delivered by Historypin and The Building Exploratory. This culminated in an exhibition in November 2018, comprising an audio-visual showcase of half of the 200 stories that had been displayed online

From bleak to chic

When John Mason moved on to Hillview as one of the first shortlife tenants, he did not think he would still be there some 40 years later.

When John Mason moved on to Hillview as one of the first shortlife tenants, he did not think he would still be there some 40 years later.

After being burgled three times in one flat he ended up in another on the ground floor near one of the entrances. “It did not take long for me to realise just how vulnerable I was when I had to take a man to A&E after he’d been attacked in Argyle Walk,” he tells me, referring to the once seedy alleyway that flanks the north side of the estate.

But as hundreds more shortlifers joined him, he found himself drawn into efforts to turn the crime-ridden slum into a thriving community and is still here to tell the tale.

There was not much room for manoeuvre, anyway. “As a single man I had no chance of getting a council flat and the private rented sector had totally collapsed,” explains John, a retired researcher and social studies lecturer.

“The beauty of shortlife housing is that it created social stability by operating as a buffer zone between homelessness and secure housing,” he adds in a Lancashire accent seemingly unmodified by decades of London life. “So although there was a housing crisis, you simply didn’t see people sleeping rough like you do today. ”

John now lives in Midhope House, in a spacious one-bedroom flat that matches his scholarly looks with its many books and papers. His bedroom overlooks a leafy courtyard where armed gangs once fought for control of turf. “Years ago my students used to recoil in horror when I told them that I lived in King’s Cross. It was the sort of thing you normally kept quiet about, ” he laughs. “Now it’s gone from bleak to chic.”

He speaks with pride about the unique style of housing management that he and other residents were actively involved in establishing on the estate with the help of the Hillview Residents Association (HRA).

CHA chief Mick Sweeney (left, seated) with housing minister Nick Raynsford and mayor Heather Johnson at regneration unveiling in 2000. T-shirted tenants indicate that relations with CHA have got off to a bad start. Courtesy, J Mason

“As an experiment in co operative democracy its record was never perfect,” he admits. “But we ran the estate in a way that was sensitive to the needs of tenants and created a very tolerant and inclusive atmosphere.”

He contrasts this with the approach of One Housing Group, formerly Community Housing Association (CHA), which took over Hillview from the council in 1994.

“It inherited a very well run estate but from the beginning refused to recognise the HRA, for many years banning us from using the tenants hall it had just refurbished.” says John, adding firmly, “However, they cannot ignore us completely.”

There have been numerous clashes, not least over One Housing’s decision to let a number of flats at market rents, more than double the social housing equivalent. John shakes his head at the mention of it. Nevertheless, for him Hillview remains a monument to the ideals of the shortlife era, when community was everything.

“It is a success story, albeit with qualifications,” he states. “It is also real privilege to be able to live in central London just across the road from the British Library and at a rent I can afford.”

Nice work if you can get it

It is a fine winter’s morning when I meet Hillview caretaker Khaled Ali, the sun beaming down from an impossibly blue sky. As we sit down to chat in the courtyard of Whidborne Buildings amid the luxuriant shrubbery it is hard to believe we are a stone’s throw from the Euston Road with its crowds and traffic. There is not a soul about and the chirruping of a bird completes the illusion of a rural idyll.

It is a fine winter’s morning when I meet Hillview caretaker Khaled Ali, the sun beaming down from an impossibly blue sky. As we sit down to chat in the courtyard of Whidborne Buildings amid the luxuriant shrubbery it is hard to believe we are a stone’s throw from the Euston Road with its crowds and traffic. There is not a soul about and the chirruping of a bird completes the illusion of a rural idyll.

“It is so nice here,” says Khaled nodding contentedly. “I love the green and the quiet. You wouldn’t think you are in the middle of the city.”

Since eight, the start of his working day, he has been busy sweeping and clearing away any rubbish, checking that the communal lights work and the lifts are clean.

Things are already looking spick and span; on a sunny day like today, positively gleaming even. When a tenant passes by he throws Khaled an appreciative glance. “If the place is not looked after properly, things quickly deteriorate and people stop taking a pride in where they live,” he explains in his softly spoken way. “I always make sure I do a good job, and residents like it.”

At work in Charlwood courtyard

But his attitude is not just down to diligence. Employed at first by an agency in 2014, Khaled now works directly for the estate’s landlord, One Housing, following the intervention of the Hillview Residents Association, which wanted a permanent caretaker on site.

“It is good for them and it is good for me,” declares the 49-year-old smiling.

“Although the agency was OK I now have job security and things like paid holidays. The residents really helped me and I am extremely grateful for this.”

Originally from Yemen, Khaled came to this country in 2006, having run a tailoring business. He now lives in Kilburn with his wife and two young daughters and loves the English way of life. “It’s so easy going here,” he says with genuine feeling.

I ask him about the war currently tearing his country apart. He sighs but tells me that his family are relatively safe in the capital, San’a.

Later he shows me around with a proprietorial air, pointing to the bin sheds where he regularly finds homeless people who’ve shacked up for the night.

“It’s become a much more noticeable problem over the last two years. I feel sorry for them especially in cold weather but you have to tell them to leave, which they usually do anyway.”

It’s break time and after a cup of tea in his cosy office cum storeroom we walk across to Midhope House, a smaller block positively bursting with greenery. There’s a spectacular splash of bird muck on the courtyard slabs and Khaled needs to remove it. I take my leave and he gives me a cheerful wave before purposefully setting to work again.

It’s my home, for better and for worse

Shola and Tyara